The Philosophy of Creating Unexpected Images

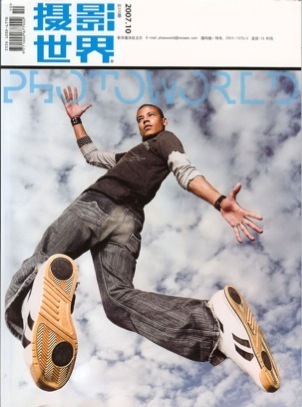

Chase Jarvis fuses the philosophy of aesthetics, technical expertise and an innovative vision to create stunningly original images.

By Ethan G. Salwen

“I am not interested in making images that have already been made,” explains Seattle,Washington, and Paris, France-based commercial photographer Chase Jarvis. “My creative vision is to shift subjects until I have created something new—something different from the norm.

This approach plays a central role in all of my work. It is what drives my passion to constantly take on more challenging and innovative projects that will keep me excited and allow me to push my creative boundaries.”

At only 35-years-old, Jarvis has already reached a level of global recognition that is impressive for a commercial photographer of any age. Jarvis is both a Hasselblad Master and a Nikon Master, and his services are in more demand than ever before. He travels the world on assignment at a frantic pace, taking on diverse assignments for clients that include Nike, Microsoft, American Express, Patagonia and Outdoor Research. Jarvis has won many photography awards for commercial campaigns and personal work; he is a board member of numerous organizations; and he is increasingly asked to speak at conferences to share his unique perspectives on the craft and business of photography.

“Some photographers shoot the same subject matter day in and day out,” says Jarvis. “That would drive me crazy. I thrive on the thrill of constantly taking on new projects and pushing my own limits.” Jarvis says that he is equally interested in shooting a single model to create one powerful portrait as he is to orchestrate a massive, million-dollar production with a crew of dozens.

“I am not selling a specific set of photographic skills,” explains Jarvis. “I am offering my unique style, which continues to develop as I grow as an artist. Regardless of the images I’m making my style comes through. And it is for my style that art directors and major companies come to me. They are excited to see how I will interpret their products and marketing needs in relation to my strong vision.”

Stylizing Authenticity

Jarvis has produced an incredibly broad range of images. Yet all of his work is tied together by a distinct, core style. “The phrase I have used to describe the thread that connects all of my work is ‘stylized authenticity,’” says Jarvis. “By this I mean that I am creating a highly considered images in which every element is carefully controlled. However, I work very hard to ensure that all of my images resonate with a true authenticity. I want to make sure that, even when it comes to my most quirky images, my viewers believe what they are seeing. The image needs to ring true.”

Jarvis uses many techniques to produce the authenticity he mentions. One simple technique Jarvis employs is simply to pay careful attention to the world around him, and not to over direct his models during shooting. “For example,” says Jarvis, “I was once commissioned to create a photograph of a surfer running from a car to the beach holding his surfboard. The shot was simple enough, and we had even created storyboards in advance. However, I did not simply start photographing to make an image that I had already preconceived.”

Before the shoot began, Jarvis took the model aside and asked him to get out of the car, remove the surfboard from the roof rack, and run to the beach. “I told him to just relax, forget about the shoot, and go through these same motions a number of times—just like he would in real life.” Jarvis examined the model’s body movements, his attitude and his rhythm. “Basically,” explains Jarvis, “I was looking for one or two gestures or expressions that would bring authenticity to the final image.”

“Once I keyed into the authentic gestures that I wanted to include in the image, I was ready to get to work,” Jarvis explains. “We styled the model’s hair and clothes, set up the lighting and basically executed the shoot the way that almost any commercial photographer would.” The difference is that Jarvis was armed with the information he needed to put real and believable elements into the image he was creating.

The Increasing Demand for Lifestyle Images

Jarvis is best known for his lifestyle and sports photographs. “These genres are increasingly crossing over and blending together,” says Jarvis. “I was lucky to be making my mark in the industry at a time when corporations were looking to market their products and services with images not specifically related to those products or services,” Jarvis explains. “This concept of using lifestyle images to market a broad range of products is growing in popularity and generating more opportunities for resourceful commercial photographers.” Jarvis notes that success in this niche market depends on having a strong understanding of popular culture, which has always been of keen interest to him.

Early in his career, Jarvis was compelled to photograph the worlds of skiing, snowboarding and other extreme sports activities. “Then companies realized that they could use these hip images to market unrelated products,” says Jarvis. “A case in point is that both Subaru and Volvo have hired me to create lifestyle images in which the cars were not the central focus to the photographs. The goal was to create images with a mood and aesthetic that was geared to appeal to a specific demographic—specifically affluent outdoor enthusiasts.”

Adding Points of Flair

While Jarvis strives to ensure that each of his images retain a feel of genuine believability, it is also true that most of Jarvis’s images contain elements that are highly stylized—visual “Jarvisisms,” if you will, that are far from anything that would be observed in the natural world. These stylized elements are incredibly unique to Jarvis’s creative vision, and sometimes they are subtle and other times they are downright bizarre. “I refer to each one of these aspects of my images as a “point of flair,’” says Jarvis. “They are something completely unusual and unique that will stand out in the photograph and give it a whole new level of depth, offering the viewer a much richer experience.”

“Although I have become very conscious about ensuring that all of my images have a point of flair, the genesis behind their ideas is probably the most organic part of my artistic process,” explains Jarvis. “High end commercial photography requires a lot of strategic thought, planning and control. But when it comes to these elements, I give myself the space to be whimsical, to have fun and to let one idea feed off another.”

Jarvis explains that it doesn’t matter if his points of flair are subtle or dramatic. “Both techniques work just as well to more fully engage the viewer,” says Jarvis. “And that’s the whole point. I am not trying to manipulate the viewer into having one experience. I am inviting them to view the image and have their own experience. I just want to ensure than I provide them with enough content so that it is a powerful experience, whether or not they like what they see.

Jarvis explains that he produces these stylized points of flair using gestures, props, composition, extreme camera angles, creative lighting, innovative postproduction techniques, or any combination of these things. “The bottom line is that anything goes when it comes to adding elements to an image that will make it truly imaginative and creative.”

In short, in his art Jarvis works to achieve an unusual level of authenticity while also integrating stylized points of flair that are strange or offbeat. “It is this playful dichotomy between the authenticity of reality and the twist of the offbeat that I strive to accomplish in all of my images,” explains Jarvis. “Really, this is what my art is all about.”

The Surprising Road to Success

“The fact that I have become an independent artist is a dramatic surprise in my life,” Jarvis reflects. And indeed, Jarvis’s story of photographic success is an unlikely one. He never assisted a professional photographer a day in his life, and he never even considered photography as a hobby until after graduating from college.

“In high school I excelled both in sports and academics,” notes Jarvis, who attended the San Diego State University in California on a soccer scholarship. “At that point in my life, my dream was to be a professional soccer player. However, I was practical enough to realize that I needed to round out my studies to have a career to fall back on.” So Jarvis decided to study to become a doctor, and earned all of his pre-med requirements in undergraduate school.

“I really don’t like to sound aloof,” says Jarvis with his typical humility. “But the fact is that school was always easy for me. I had no problem with the pre-med coursework even while spending four hours a day practicing soccer.” However, Jarvis began to sense that becoming a doctor did not best meet his personality. “Frankly,” he says, “I was going through a major evolution in my life. In college, I was getting exposed to radical new ideas, and I realized that I had no idea what I

wanted to do with my life.”

A critical development for Jarvis occurred in the beginning of his third year of college when he took a philosophy class. “I had always been into nerdy thinking,” admits Jarvis. “I was always curious about the bigger questions about the world and existence. But I fell in love with philosophy, and so I worked like a madman during my final years in college to earn a double

major in pre-med and philosophy.”

“The thing that interested me most about philosophy was the philosophy of aesthetics,” says Jarvis. “My eyes were opening to the idea that the subjective value of judgments of assessing images was as complex as other moral and ethical systems of value-based thinking.” Jarvis was utterly intrigued by the interplay of these concepts, and during his final year of college he read scores of biographies about artists.

“I attribute much of my interest in such concepts to my parents,” says Jarvis. “My father was a policeman and my mother was an administrator. Neither one of them completed college, by they were both intelligent and curious. We were by no means rich, but I was an only child and my parents were deeply concerned that I get the best education I could. They also insisted on exposing me to the world of ideas beyond our local community in Seattle.” At a very young age Jarvis’s parents began to take him on family trips to exotic locations, including Tahiti, Mexico and Europe.

“I was probably only seven when we visited Tahiti,” says Jarvis. “It might sound naive, but I was totally amazed that there were people speaking to each other in a completely different language. It was mysterious and exciting, and it was something that I wanted to better understand. It was something that I wanted to be a part of.”

“In the early 1980s, when I was in the 7th grade, we traveled to Europe,” recalls Jarvis. “I’ll never forget being exposed to the wild sights of Piccadilly Circus in London. The punk rock teenagers with their bright, dyed mohawks peaked my interest in popular culture. And I’m sure that relates directly to the why I am the popular culture junky that I am today.” Indeed, a cutting edge sense of popular culture runs through almost all of Jarvis’s images. “I tip my hat to my parents,” says Jarvis gratefully. “By taking me on exciting journeys at a young age, they infused me with a curiosity that continues to inform and inspire my life and craft.”

The Birth of a Unique Photographic Vision

“Frankly,” admits Jarvis, “I was never really that interested in any particular photographers as role models or inspirations. In college, when I began to study the philosophy of aesthetics, it was the modern artists based in New York in the 1940s, 50s, 60s and 70s that truly excited me,” Jarvis remembers. He lists Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jim Dine, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollack and many others thought-provoking heroes. “These visionary artists were not just making art,” says Jarvis with enthusiasm. “They were actually redefining the very meaning of art.”

Jarvis says that he was enamored by the do-it-yourself mentality of these artisans and their ability to turn the entire art world on its head. “Marcel Duchamp’s famous urinal had a huge impact in my life as an artist,” says Jarvis. He is referring to the fact that in 1917 the French artist signed his name on a common urinal and hung it on the wall of an art exhibition in New York City. Duchamp’s so called “readymade” art was a sensation that shocked and outraged

In Search of a Calling

Jarvis was filled with enthusiasm for the potential of art when he graduated from college in 1994, but he was still a little bit lost in terms of the direction of his own career. “I had not yet stumbled onto photography as my calling. “I felt a responsibility to society to work at a respectable job,” Jarvis explains. “So I applied to medical schools even though I was fairly sure that I did not want to be a doctor.”

After college Jarvis made an extensive, eight-month trip through Europe with his girlfriend, Kate, who has since become his wife and executive producer. “Right before the trip I inherited from my grandfather one of the early Minolta 35mm autofocus cameras with a handful of lenses,” Jarvis explains. “I photographed extensively during the trip. And at 23-years-old, this was truly my first foray into any kind of real photography.” Jarvis found that he had a natural ability to create clean compositions, and the technical basics of photography came easily to him. “Still,” says Jarvis, “It’s fair to say that I was doing little more than taking fairly typical travel snap shots.”

“I still remained almost entirely focused on the concepts relating to the aesthetics aspects of image making,” recalls Jarvis. “I wanted to make nice pictures, but I was not dedicating myself in any serious way to actually becoming a photographer myself. I was more curious about the concepts of how I could transform reality of what I saw traveling through the photographs I was

taking.”

The Steamboat Revelation

On returning to the United States, Jarvis moved with Kate to Steamboat Springs, Colorado, where they lived as “ski bums.” They worked a few nights each week waiting tables and earned enough cash to spend most of their time skiing and enjoying themselves. However, it would be a misconception to think that Jarvis was actually in any way a bum during this period.

Using his Minolta 35mm SLR, Jarvis started photographing friends and professional skiers on the slopes. “I really can’t explain what happened,” says Jarvis. “But something just clicked inside me. I began to photograph with incredible passion, and I became totally obsessed and committed to photography.” With his typical focused and organized manner of synthesizing information, Jarvis set about the task of mastering the craft of photography. “It was during this phase of my life that I that realized with 100 percent certainty that I wanted to be a photographer,” says Jarvis. “However, in retrospect I wasn’t yet ready to admit this to myself.”

“I have always learned better on my own,” says Jarvis. “And when I wasn’t photographing on the slopes, I practically locked myself away, devouring every book and magazine about photography I could get my hands on. Jarvis’s photographic preoccupation was to imitate and improve upon the work he saw in ski magazines. He shot with Velvia chrome film to achieve rich, saturated colors. He also set up a black and white darkroom in the bathroom to teach himself that skill set.

“The time at Steamboat really served as my own, personal, self-directed photography school,” recalls Jarvis. “I was obsessed and learned quickly. My photography was very intentional. I focused on capturing peak action and creating images with really solid, clean compositions.” Jarvis was making some striking images, and even licensed a few to ski companies. “But I still

wasn’t clear on what direction I would go in. And I still felt the ache of responsibility to continue

my schooling.”

After two years in Steamboat, in 1996 Jarvis and Kate moved back to Seattle where Chase enrolled in the University of Washington. Jarvis entered one of the top graduate philosophy programs in the country to continue his studies in the philosophy of aesthetics. “I enjoyed the coursework and the reading,” says Jarvis. “And it helped me a great deal in learning how to discuss the power of images in a way that few photographers can. But to be honest, even then I knew I was just buying my time.”

Jarvis explains that he knew that his future lay in photography, but he wasn’t sure how to proceed. He continued to hone his craft in isolation, and became increasingly clear that he would not finish his doctorate program in philosophy. “In many ways,” admits Jarvis, “I realized that I was just waiting until my dream job came along and hit me over the head with a hammer.

many art critics. However, Duchamp’s bold move also opened new doors of creative possibilities for future generations of artists, including many of the modern artists that Jarvis would come to admire.

“Duchamp loved to break rules,” explains Jarvis with enthusiasm. “Duchamp named his urinal sculpture ‘Fountain.’ When explaining the concept of the ‘Fountain’ Duchamp said, ‘This is artifice. This is an illusion.’” Jarvis says that Duchamp changed the very nature of an object simply by deciding to view it in a different way. “That is what has always thrilled me about the process of making art,” says Jarvis. “More than anything else, it is the intention behind the act of

making art that matters.”

Although Jarvis has never compared himself to Duchamp, he definitely sees himself as a rulebreaker. And he is very aware that much of the art he creates is an illusion.

The Intersection of Art and Business

Jarvis’s dream job hit him over the head with a hammer when he met a person in the marketing department at REI, the worldwide, famous recreational outfitting company based in Seattle. “I was working in the REI ski shop tuning skies to make a few bucks while in school,” says Jarvis. “REI was in the middle of building a massive flagship store in Seattle, and they needed mural-size action images to place all over the store. I had already put together a portfolio of my images from Steamboat, and the marketing person was amazed.”

REI licensed a number of images from Jarvis. They also asked Jarvis to shoot more images on spec, which he did over the next week. “With that one job,” says Jarvis, “I made more money than I had in some years. That was really the wake up moment of my career. I realized that photography was a serious option and that I could make serious money in this field. Within a few months I had hatched my plans for my photography business and dropped out of school.” That was in 1997 and Jarvis has been rocketing forward ever since.

“It was a big moment when I started calling myself a photographer,” says Jarvis. “I had been working hard at making images, but now I was announcing that this was how I was going to make my living, that this was who I was. Just speaking that way inspired me in a completely new way. I became an information-devouring machine, and I attacked photography with every bone in my body. I put the pedal to the metal, and professionally I haven’t really thought about much else since.”

Reverse Engineering the Business of Photography

At the same time Jarvis was devouring the techniques of photographic image making, he dedicated himself to learning the business of photography. “I was never turned off by the business side of photography,” says Jarvis. “I simply saw it as another creative challenge.” Jarvis believes his business success was the result of three things: He had developed a unique ability to talk about the power of images while studying the philosophy of aesthetics; he understood the intersection of art and business; and he is a “people person” who is able to connect with creative and business people of all levels.

“There are great artists who can’t talk their way out of a sack,” says Jarvis, commenting on the fact that many skilled photographers simply do not know how to make money. “On the other hand, there are business people who can sell ice cubes to Eskimos.” Jarvis knew that he could make great images. But he realized that excelling in business practices was yet another key to his truly making it as a successful photographer.

“When I was first starting up my business, I basically reverse engineered the notion of how to make money through photography,” says Jarvis. “I realized that there was a problem to be solved: How to make the most money with my images? And I have always been good at solving problems.” By “reverse engineer” Jarvis is referring to the fact that he understood that in different contexts the same image could be licensed for drastically different sums of money. The solution Jarvis arrived at was to go directly to companies that would be interested in using his images to market their products.

“A lot of photographers feel the need to start out slowly,” says Jarvis. “They try to sell one image to a magazine and then another and then another. They hope to eventually be able to have enough of a portfolio to be able to approach ad agencies to get bigger assignments, or to be able to get higher paying editorial work. That was not my approach at all.”

Jarvis parlayed his success with REI and went directly to companies to provide images for packaging and other marketing collateral. “I figured it would be way cooler to make a lot of money selling an image to a backpack company that no one had ever heard of then to make no money getting my name in a popular magazine,” says Jarvis. His approach worked, and within a surprisingly short time he had made more money than he had imagined possible. “Even more important,” says Jarvis, “I now had the images to be able to go to agencies and magazines to get the big assignments.”

The Artistic Freedom of Commercial Photography

Through all of this time, Jarvis never lost sight of the passion that compelled him to photograph in the first place: his interest in the philosophical underpinnings of what makes a powerful image. “Commercial photography is a great realm for exploring art because there is no concept of being beholden to creating a documentary image, which has seldom interested me,” says Jarvis. “Yes, I am interested in creating authentic images. But I am more interested in creating images that have an incredibly strong sense of style. And I put no limits on how I create this style—in camera or in postproduction.”

Jarvis notes that the digital revolution in image making has allowed him to engage in an artistic process much like the painters he admired while studying the philosophy of aesthesis in college. “When I was reading those biographies in college about the New York artists that were pushing boundaries, I was blown away by their ability and eagerness to break boundaries and to redefine art,” says Jarvis. “Now I am lucky to find myself in a similar position.”

One aspect that defines Jarvis’s approach to photography is that he likes to mix things up, and he will do just about anything to keep his art fresh and unique. “One way I work to keep things compelling is to look for new angles and to think about ways to present familiar subject matter in an innovative way,” Jarvis explains. “I have rented a 50-foot man lift so that I can photograph athletes from above; I have constructed a massive, acrylic see-through floor so that I can photograph athletes from below; and I have photographed stylized golf scene’s at night.”

Another way Jarvis keeps his images riveting is to constantly keep on top of camera and imaging technology. “Constant change in equipment and postproduction techniques are now simply a regular part of the modern photographic process,” says Jarvis. “While some photographers are frustrated by the constant change, I am thrilled by the endless possibilities offered me by these new developments.”

The Best Hammer for the Job

“The camera does not make the photographer,” says Jarvis. “However, good equipment is critical for success in the business of photography.” Jarvis says that if there were one thing that he would have done differently in his career it would have been to invest in better equipment earlier on. Jarvis currently works with incredibly high-end equipment. “I like to think of a camera as a hammer,” says Jarvis. “It is just a tool. But you’ve got to know how to use it very well to get the most out of it.”

Jarvis works with two different camera platforms. One the Nikon D2X, of which he has a number of bodies and tons of glass, including the following lenses: 10.5mm, 16mm; 17-35mm, 17-55mm; 20-35mm, 28-70mm, 50mm, 85mm, 70-200mm; 80-200mm, as well as a handful of teleconverters. Jarvis also shoots with the Hasselblad H2D, for which he has a couple of digital backs and the following lenses: 35mm, 80mm, 150mm, and a 50-110mm. “I have a film back,” says Jarvis. “But I never use it. And I almost always shoot directly to memory cards, and almost never tether the camera to a computer.”

“The Hasselblad is my primary tool of choice,” says Jarvis. “I love the 6 x 4.5 ratio of the image, and the 22 megapixel file the camera produces is absolutely gorgeous. The Hasselblad glass is incredible, and the leaf shutters in the lenses allow me to synch my strobes up to 1/800th of a second, which gives me a lot of flexibility when shooting with strobe on location.”

Jarvis has actually made a name for himself by using his Hasselblad in environments for which the manufactures never intended it to be used. “People tend to think of a Hasselblad as a studio camera, or only fit for very controlled outdoor environments,” says Jarvis. “But I’m a rule-breaker, and the first chance I got I took the Hasselblad out to the slopes and started shooting snowboarders. Why not? The technology is incredibly and I want the best looking images I can produce.”

“I tend to shoot with the Nikons when I need speed and when I’m machine-gunning away with the motordrive,” says Jarvis, who notes that the Hasselblad will only allow him to shoot about one image a second, while he can shoot five to eight frames per second with his Nikons. He also tends to use the Nikons when he is shooting higher volumes of images with less controlled lighting setups.

Lighting Masterfully

Jarvis is a master of lighting, and when he is working with his Hasselblad he seldom uses fewer than four strobe heads. “I primarily work with the ProPhoto 7Bs,” says Jarvis, explaining that they are battery powered. “This gives me the flexibility I need I need to work on location. I also use the ProPhoto 7As for when I need more power.” Jarvis also uses a ProPhoto HMI hotlight which is daylight balanced and provides continues output. He says it’s a fantastic piece of equipment because he can control it with precision while mixing it in with his strobes.

“I light dramatically when it’s called for and I light like it’s natural when that’s called for,” Jarvis explains. He says that it’s more fun to light dramatically but that such lighting is only appropriate for certain images. Jarvis says that both approaches to lighting require skill, experience and confidence. “I have good lighting skills,” says Jarvis. “And I like to get lights set up fast and move on to the shooting.”

“You can noodle lighting to death,” says Jarvis. “You can worry about the tiniest little details. But I try to not be a spaz about that stuff. I pride myself on being able to do it quickly and then getting to the images.” Jarvis says he orchestrates 100 percent of the lighting efforts on his shoots. But at the same time,” Jarvis says, “I always look for feedback, and I always listen to ideas from the talented guys I’m working with. I like the collaboration.”

Collaboration is the Name of the Game

Jarvis has anything but a “closed door” policy when in comes to seeking input. “If one of my crew members sees something they think can be improved, I mandate that they speak up,” says Jarvis. This is one thing that definitely unique about Jarvis in the world of commercial photography. “For me,” says Jarvis, “Art is a collaborative process. I have done very well in this field, but I would not have been able to achieve this level of success were it not for the efforts of a lot of amazing people working in concert.”

Jarvis is an extraordinary image maker and a natural leader, but he is down-to-earth and modest. “I have tremendous respect for the people I work with,” says Jarvis. “I think this might have to with the fact that I had to make it on my own. Because I had to figure out the industry on my own, I remain very committed to the success of younger, up-and-coming photographers.”

Just Warming Up

“In many ways I feel like my career is only just beginning,” says Jarvis. “I have gained mastery of the photographic process; I have developed a style and approach to making images; I have established an amazing spectrum of clients; and practically every day I am taking on new and more challenging projects.” Jarvis says he feels lucky to be in the right place at the right times in terms of the development of digital image making and the evolving nature of the Internet.

“For many years I used to comment somewhat forlornly about Andy Warhol’s creative factory in New York City,” says Jarvis. “I used to think about how exciting it would have been to have been a part of that scene, that energy, that creativity. Only just recently have I started to realize that I have actually built my own creative factory.” And then pausing, Jarvis adds, “To be honest, I’m actually amazed by the position I find myself in to be able to create amazing, unexpected images.”

Ethan G. Salwen is an independent writer and photographer based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.